November 22, 2024

By

Ronald V. Morris, Department of History, Ball State University

Denise Shockley, Gallia-Vinton Educational Service Center

Correspondence should be addressed to Ronald V. Morris, Department of History, Ball State University, Muncie, Indiana 4730. RVMorris@BSU.edu

Abstract

Every year, 35 secondary social studies teachers from southeast Ohio, part of Appalachia, participate in a unique summer professional development program. Traveling through Wyoming, Idaho, and Montana by air and bus, they engage in in-service activities that promote personal reflection, professional growth, and exposure to new historical and geographical contexts, enriching their teaching practices.

Participant reflections highlighted key themes, including the value of diverse learning environments, the importance of addressing controversial issues, and the role of experts in enhancing content. This study is particularly relevant to rural educators, addressing challenges like limited travel opportunities and emphasizing the need for broadening perspectives through professional development.

The findings underscore the impact of experiential learning on teaching effectiveness, demonstrating how travel-based programs can deepen teachers' content knowledge and improve their ability to engage students. This research contributes to understanding effective professional development for social studies educators, showcasing the benefits of immersive, travel-based experiences.

Secondary Social Studies Teacher In-Service Revisited

Every year, a group of 35 secondary social studies teachers from southeast Ohio, a region within Appalachia, participates in a unique summer professional development opportunity. They travel by air and tour bus to explore Wyoming, Idaho, and Montana, enhancing their teaching and learning through professional development. In their reflections, the teachers discussed experiences and revealed several patterns about what they consider important about in-service for secondary social studies teachers.

This program aimed to enrich social studies teaching by encouraging Appalachian teachers, who typically do not travel, to explore new places and learn on location.. The significance of the study was to help teachers learn social studies content and have broadening experiences to expand their perspectives as they considered instructional practices they shared with their students. While lots of money was spent on professional development in comparison to other subjects, little was spent on secondary social studies in-service, and it was important to determine what perceived benefits derived from the programs.

Morris (2017) described the in-service, the process of providing additional knowledge, skills, values, and dispositions, how the in-service achieved this, and to document what resulted seven years after the trip. While the experience was common to the group, how they encountered the events of the trip was unique to each person. Similar ideas clustered into teacher thoughts that reflected what they encountered during the in-service. Teachers reported ideas that contributed to assertions and trends about the nature of this experience and t identified the key themes that emerged from the experience of the teachers during their in-service training program. These assertions and trends assisted the researcher to answer the question, how did secondary social studies teachers interpret professional development delivery through a travel experience and what travel experiences result from it?

Description of the In-Service Training Program

The program aimed to teach the differences between conservation and preservation and their roles in modern political debates, through guided field trips outside Appalachia. The teachers learned through a guided field trip what life was like outside Appalachia. Since many of them had limited opportunities to travel outside Appalachia, this experience helped them to learn more about what the American people and land were like in different places.

This was the eleventh year of high impact summer teacher in-service called Landmark Moments Field Studies provided by a regional educational service center. The professional development addressed specific pedagogical content knowledge by examining three themes:

- How were the western national parks formed?

- How did Americans see the West from exploration, to art, to photography?

- How is land management contentious today?

The director of the service center planned a four-day professional development program with a local professor, followed by a weeklong trip where teachers learned about the land. They prepared for the weeklong travel with four days of teacher in-service prior to the trip where teachers learned about the land from a professor. The teachers received readings and curriculum materials to prepare them for traveling. The director of the educational service center planned one week of direct experiences on location for teachers to interact with university professors and tour guides.

The director selected tour guides and guest speakers based on their reputation and local university profiles. Presentations were provided by a folklorist, local experts, and park rangers. Each year the director tried to take the teachers to a new area, selecting indigenous foods, accommodations, natural wonders, historic sites, local cultural sites, and events that would give the teachers direct and high impact encounters with the natural environment.

Teachers engaged in on-site activities during the professional development. They visited Glacier and Yellowstone National Parks with rangers. They met a folklorist, experienced ranch campfire lore, and visited local theater interpretations of western legends. They visited the Conrad Mansion, western art at the Russell Museum, western exploration at a Lewis and Clark site, and western animals at the Grizzly and Wolf Discovery Center. Teachers also toured the Montana State Capitol and visited with Governor Bullock. They could explore the land in various ways including walking, riding, boating, roping steers, paragliding, or rafting on the Snake River.

Methodology

Teachers initially volunteered for a grant program, and even after its discontinuation, they continued traveling through the educational service center. New participants were nominated by their principals, with little turnover in the last decade. Teachers could earn continuing education credits or renew their licenses through this program. The authors included the director of an educational service center and a university social studies professor who did not participate in the program.

At the conclusion of the trip, participant educators created open reflections on his or her experiences. Most participants used the travel time home to compose their thoughts which they emailed to the director of the educational service center. Researchers had access to the reflections after the trip, and they identified sub-assertion patterns. Frequency counts of the largest representation of ideas mentioned in common determined the assertions. Reflections varied in length from six sentences to a single-spaced typed page. The researcher employed inter-rater reliability during the coding process, which yielded the frequency counts noted in parentheses in the findings below. Reflections were analyzed using open and axial coding to identify patterns in responses, which informed the development of sub-assertions, assertions, and overarching trends, aligning with the principles of grounded theory methodology (Baily & Katradis, 2016). Once sub-assertions, assertions, and trends were identified, researchers provided an example of the idea which they reported. The combined patterns supported assertions, and the combined assertions allowed trends to appear (Heineke & Neugebaurer, 2018). Trends were triangulated against other reflections. The researchers continued to discuss ideas in the remainder of the section (Sutimin, 2019; Harmon et al, 2018). Seven years after this in-service program, the same teacher sample was surveyed to reveal what travel opportunities the teachers had utilized. Two teachers had retired, and two new teachers had joined the group. One yes or no question and open-ended questions asked the teachers to elaborate on their survey responses.

Participants

Thirty-five white teachers from six school districts participated, including twenty-two males and thirteen females. Most taught high school, and all had at least a bachelor’s degree, with twenty-eight holding master’s degrees. While most had been raised and educated in Appalachia, all these teachers lived in a remote, economically depressed area with low educational attainments, requiring extraordinary measures to attempt to alleviate the effects of rural poverty in their community. They had participated in the program for eleven years and looked forward to continuing. Pseudonyms were used to ensure confidentiality.

These educators experienced Appalachia. They grew up, attended school, went to college, and found a job locally with no time spent away from the region. Since the teachers and their students’ way of life was Appalachian, they were not able to contrast that to life outside the region unless they identified where Appalachia was and appreciated what made their culture unique as it changed and diversified. The lack of high school graduation experience in adults and the consummate parental awareness and support in the transition was key. Career preparation sometimes did not align with job availability and providing additional options for non-college track students remained challenging. After high school, students faced multiple challenges in transitioning into their next phase of life (Kannapel, & Flory, 2017). Limited opportunities due to poverty constricted educational attainment and employment options challenged Appalachian youth. While youth desired to remain in Appalachia, graduation rates had improved, and programs existed to help. The rigor and nature of high school preparation coupled with a lack of place-based approaches raise concern about the abilities of Appalachian students to be competitive at the university level. However, college was sometimes a difficult transition due to the oral language habits that invited stenotypes and prejudice (Dunstan & Jaeger, 2016). Inclusion programs needed to consider dialect patterns as a function of diversity.

Findings and Discussion

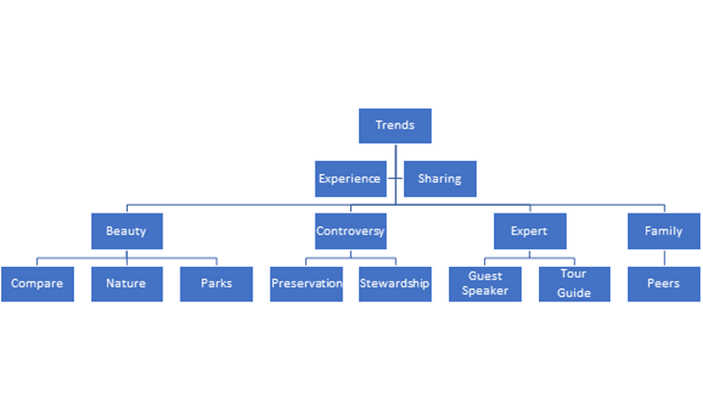

Teacher reflections highlighted themes like comparisons (12), guest speakers (6), national parks (25), nature (6), peers (15), preservation (7), stewardship (19), and tour guides (5). Figure 1 illustrated how sub-assertions supported assertions and trends

Figure 1: Sub-Assertions, Building to Assertions, and Trends

Sub-Assertion

Comparison

When teachers compared places, they made connections from their home to the experience in the northern Rocky Mountains. They made comments such as:

As Appalachia offers her own distinctiveness, I plan to not only explore these aspects associated with the Rockies, but compare and contrast them to our homeland. What lessons and ideas we have to examine and celebrate. Just as the Old West is being challenged (and arguably prospered) with the New, might Appalachia, and Gallia County, grapple with and explore these similar ideas. (Aaron, 2018).

Educators compared the issues or landscape with their Appalachian home. The contrast between the two areas allowed them to examine what they encountered in relationship to what they knew. When comparing the areas, they found parallels and discrepancies between the two locations.

Nature

The teachers referenced the experience in nature. Direct encounters with the land was an important part of the trip for them because it was a way of interacting with the land that was both foreign and familiar to them. “The experiences of the week had us arriving in Montana where we rode horseback over the trails and experienced nature while gaining valuable information on Glacier National Park (Roaby, 2018).” The educators experienced nature in their home community, but the environment looked different in a new location. Compared with their views, limited by extreme foliage for half the year, the open spaces of the West looked unique and different. However, the contemplative aspects of their nature at home manifested in solace and inspiration continued in different locations.

National Parks

Teachers raved about the national parks. Sometimes, they commented about the national parks, talked about another important subject, and came back to the national parks. Their statements included lines such as, “The National Parks were unbelievable” (Jayne, 2018). The educators experienced the national parks as a concept, by their scope and breadth, and by the ecosystems encompassed by the parks. While some of them encountered eastern or historical parks, this was the first encounter with the western national parks. The teachers’ encounters startled them.

Preservation

Preservation seemed to be the same as stewardship as the teachers were writing about it. The teachers wanted to preserve the scenery so that their students could see it; it was a noble sentiment, but difficult to ensure in a world with rising temperatures and western fires. “Nature conservancy, preservation efforts, and national parks designations ensure that all generations will be able to enjoy these wonders” (Mark, 2018). The teachers were very interested in the future and making sure that the others could receive the same benefits they had accessed. This idea of preservation was different from the original idea for the national parks -- conservation. Conservation was the management of resources so there was a constant supply of, for example, buffalo to hunt. Preservation in this case was wanting to find all the resources untouched.

Stewardship

Teachers identified stewardship as an important part of the trip. Stewardship was the active conservation of flora and fauna for the next generation so future visitors could enjoy what the teachers were seeing. The teacher participants on this trip represented a demographic that did not typically endorse big government; however, they did not take a libertarian perspective on this issue. Despite initiatives to remove protections for national parks and natural resources, the teachers refuted that approach. As a result of the in-service, they wanted to make sure an element of stewardship was present to ensure the land was present in the future.

On our visit to Yellowstone National Park and Glacier National Park, we got to see the importance of protecting the natural resources. Without the government setting aside this land and protecting the natural resources that can be found there, who knows what we would be left of these lands, and the animals that call it home. Our government’s foresight and concern for these lands made it possible for me and future generations to experience and enjoy these beautiful sights. (Ryan, 2018)

The teachers wanted to make sure that a responsible party was in charge to save and maintain the land. They expressed an interest in making sure that the landscape was sustainable and for multiple generations to get to see it. The preservation, stewardship, and conservation were all part of the values the teachers aspired to communicate to others.

Guest Speaker

The guest speakers passed along information about the site to interpret the land and culture to the group of teachers. The teachers met a variety of guests including historic home interpreters, a folk singer, a governor, and a national park ranger. The educators greatly appreciated these people as an important part of the trip. The teachers made comments such as, “The visit with the Montana Governor was outstanding. Stephen Clark Bullock gave us a great insight into the educational processes in his great state” (Vicky, 2018). As part of the tour the teachers encountered local experts and docents. The teachers learned from all of them and found the guest presenters to be important components of the way they understood the experience. The commentary from the guests helped shape and frame the experience in the minds of the teachers.

Tour Guide

The teachers found the role of the tour guide to be important to interpret the experience before and after it occurred. The tour guide provided additional context to the teachers as part of the field study. “Dr. Dan Flores was both a visiting professor for our autumn workshops and doubled as our tour guide. This combination has enabled me to understand more fully the importance of national parks and preservation (Mark, 2018).” The tour guide prepared the teachers prior to the trip with multiple days of instruction about the places they were going to visit. They also made sure the teachers understood what they were seeing out the windows of the bus by commenting on civic, economic, geographic, or historical commentary. The tour guide helped the teachers understand some of the items they later discussed as the most important parts of the trip.

Peers

The teachers responded to their peers as they traveled with them on the trip. Some of the teachers they worked with every day in school, but others were from different school districts. They may have taught similar topics, have similar community issues they deal with, or have similar backgrounds despite their only seeing each other only a few days per year.

Like most years the collaboration and connections made with 50 great educators of this region of Ohio is so rewarding. Having conversations about how to reach students, and how to expand their learning cannot be overstated. I love the opportunity to learn what they’re doing in their classrooms covering a wide verity of content and sharing what has worked in mine. Landmark Moments is not just a Field Study it truly is a learning community/family that will have lasting impact for generations. (Brent, 2018)

The informal and teacher-initiated content and pedagogical in-service that the teachers engaged in was very meaningful for them. The conversations flowed back and forth between peers in this sphere.

Assertions

Beauty

Combining the categories of comparison, national parks, and nature resulted in the assertion of beauty (eighteen). The teachers responded time after time to the idea of nature and national parks as being beautiful, aesthetically pleasing, and highlighting the magnificence of the land.

Beautiful, awe-inspiring, and stunning are adjectives that can't grasp the grandeur that these places hold, places that have captured the imagination and minds of explorers, artists, scientists and everyday citizens and will long continue to do so. I am amazed by the vastness of our country and the beautiful natural and cultural varieties that are intrinsically linked to these lands. (Aaron, 2018)

They encountered the land as being beautiful beyond their experience that transcended their minute existence. The incomprehensibility baffled them as did the scale of what they observed. The interactions they had with the land helped them to see the land in different ways: through the eyes of many people who encountered the land for the first time.

Controversy

The teachers recognized the element of controversy in what they experienced (fourteen). Both stewardship and preservation was only one path and other competing interests desired to use the land in different ways.

There are so many environmental issues that are relevant today in the news. The reintroduction of the wolves, fire control, and the threat of a volcanic eruption. Students can research, debate, and discuss issues concerning current laws for the protection of the lands from oil drilling, fracking, water control, timbering and protection of the animals. I can propose the question of how to control the large volume of visitors to the park and to design solutions. (Kim, 2018).

Mineral extraction and tourism were only a couple of ways people desired to use the land. Since these lands were held in trust by the government, these enduring issues were encountered by every generation who decided them again. Redefining the issue and solution for each generation required informed and engaged citizens.

Expert

Combining the sub-assertion of the tour guide and the sub-assertion of the guest speaker resulted in the assertion of the expert (sixteen). Teachers found the expert to be a crucial source of knowledge. “We have access to top history researchers and presenters . . . (Gina, 2018).” Many teachers saw themselves in this role in the classroom as they returned to convey information to their students. Even though teachers were engaged in professional development far from their home they were always thinking and talking about their students. The teacher as expert was an interesting construction of knowledge that they reinforced from the field studies. The commentary provided by the expert materialized in the reflections of the teachers as they came to know the field study. The expert posed questions and raised issues on site and teachers found their own answers and raised their own questions. The change from information broadcast to reflective inquiry changed the nature of the teacher in-service.

Dr. . . . a visiting professor for our autumn workshops . . . doubled as our tour guide. This combination has enabled me to understand more fully the importance of national parks and preservation. We discussed some of the political and social ramifications of preservation. I will be able to not only show my students the beauty of the Northwest but also the impact of President Teddy Roosevelt, John Muir, and others on the movement. (Mark, 2018)

Teachers identified issues and controversies tied to land policy. The expert tied influential figures into present issues. The teachers raised questions based on their experiences and the narrative provided by the expert.

Family

The teachers engaged for two weeks with individuals who cooperated for the good of the group to accomplish the goals of the group (twelve). They defined this group process as a family.

Everyone in our group is like a family and we truly enjoy each other’s company. Our conversations we have on the bus trips and airplanes are so precious. The moment I spent with the group at the waterfalls of Yellowstone was truly moving. I feel so blessed that we have such caring and motivated people teaching our children. I will miss them and can’t wait to see them next year. (Bill, 2018)

They were genuinely going to miss each other but looked forward to the prospect of a family reunion. These educators shared an interest in professional and personal conversations in a variety of locations. Furthermore, they shared a familiar context of working based in their Appalachian home.

Trends

Experience

The trends that immerged from the assertions reflected the ideas of experience (twenty-seven) and sharing (twenty-three). The teachers had the experiences of a family in experiencing beauty and exploring controversial issues together. “Thank you for this experience. I cannot imagine any group of teachers in this country who have had richer experiences. My teaching has reached a higher level because of these experiences (Gene, 2018).” The teachers engaged in a series of events that enticed them to grow, challenged their beliefs, and motivated them to improve their teaching. In addition, they found meaning in these experiences. Part of the value of the program was the experience itself with supportive peers, encountering a new kind of beauty for the first time, and contesting new ideas.

Sharing

The other valuable part of the experience was the process of sharing. Both sharing in the peer group and the sharing they were looking forward to doing with their students.

I have been able to capture the attention of many students who had no previous interest in social studies or who did not consider exploring the world beyond their own experiences simply by sharing my stories and pictures of the places we have visited. Having someone they personally know introduce them to new places, people, and events through firsthand experience and materials, I have found, has a much greater impact on students than any professionally produced documentary and textbook. (David, 2018)

The teachers shared beauty, the events with their peers, and the tension of these ideas together. The teachers prepared to share the magnificence of the land, the confidence of their peers, and the controversial ideas of preservation and stewardship to their students. In experience and sharing, the teachers engaged in professional development in field studies.

One discrepant case was particularly puzzling. It would be interesting to explore further into this comment to determine more about the thinking behind the statement. When describing an obscure exploration story one of the teachers observed, “I envision using that story to examine the political spin that happens to history with my students (Brian, 2018).” It could be that the teacher was looking at differing perspectives of people at that time and rival priorities or it could be that the teacher has a revisionist agenda. Either way it would be interesting to determine what the teacher was thinking and how they would explain their observation to students. This was the only person to make this observation, but it was interesting to note.

Teachers returned to places where they had visited as the group. Once they explored a place in a group and it became comfortable to them, they desired to share that same place with others. As Pace (2019) noted their early aversion to risk taking and venturing into unknown territory was ameliorated.

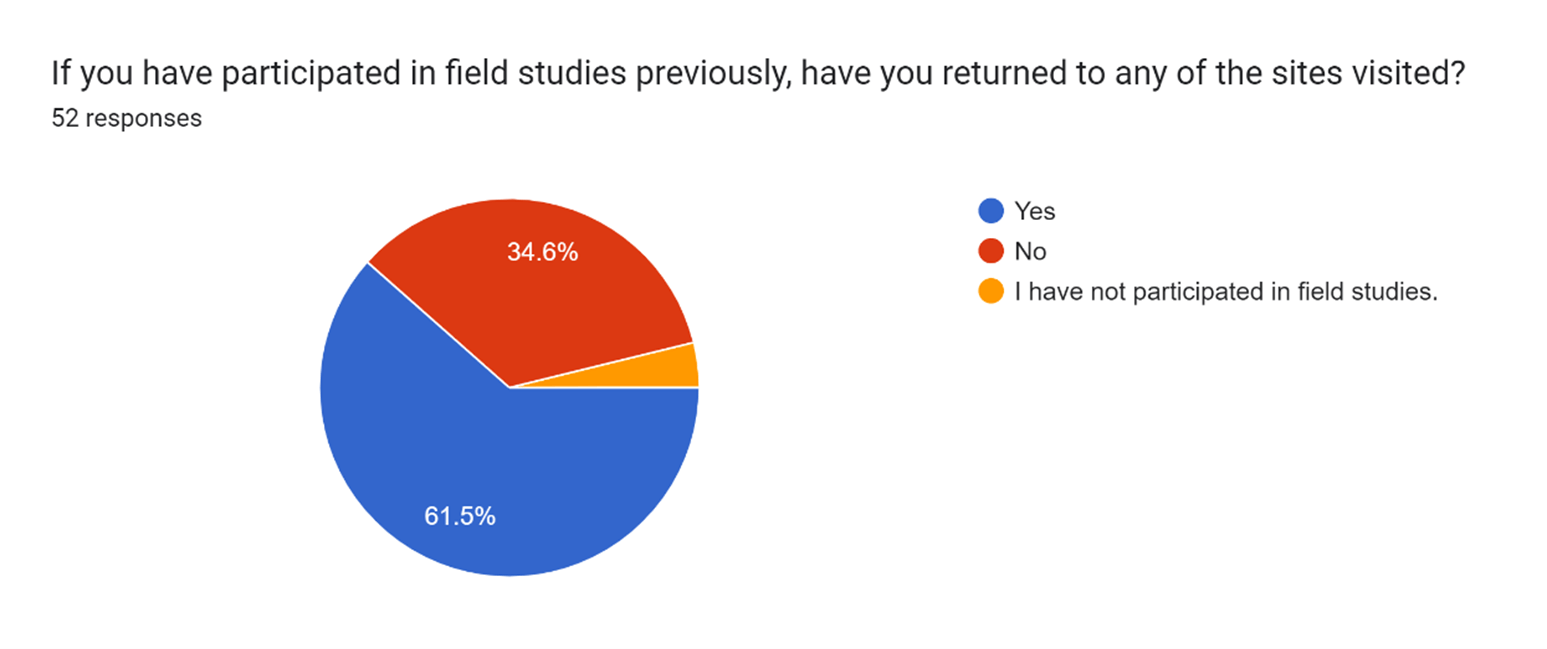

Figure 1: Return to Historic Sites

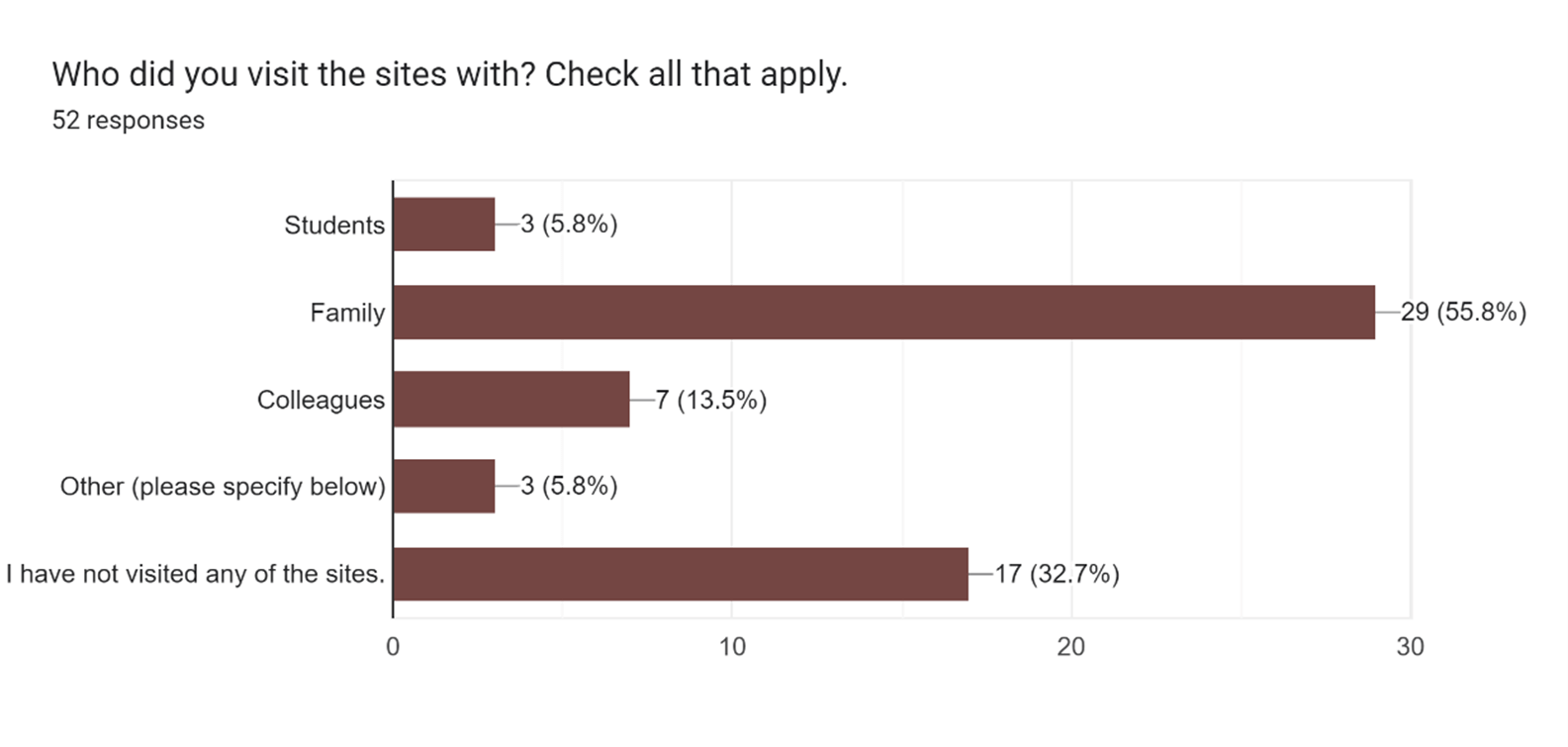

The program was successful in getting teachers to visit places that were included in the curriculum that they taught. Slightly over half (55.8%) returned to the site with their family and shared the site with their family.

Figure 2: Sharing a Site with Others

However, nearly a third of the participants (32.7%) did not return to any of the sites. Interestingly 13.5% returned to the site with colleagues, presumably people who also taught about this subject. Disappointingly, only 5.8% shared the sites with their students, but every teacher who was able to visit had a defining experience. The comments reflected that with just a couple of exceptions all the travel was east of the Mississippi River which was closer to their homes.

Classroom Practice

Adam, an eighth-grade teacher, shared his summer learnings with students, referencing state social studies standards on historical tourism. He discussed the balance between encouraging park visits and preserving the parks, a public policy question reinterpreted by each generation.

Adam wanted his students to ask a different question for historical tourism for each of the discipline areas of civics, economics, geography, and history. He also found standards from the C3 Framework that supported multiple disciplines that supported his curriculum. The development of the western part of the United States paralleled the development of railroads. In 1872 Yellowstone National Park was established, and students asked the question: How do you get there? This question was framed by geography, “D2.Geo.2.6-8. Use maps, satellite images, photographs, and other representations to explain relationships between the locations of places and regions, and changes in their environmental characteristics” (NCSS, 2013). As the railroad looked for additional sources of revenue, it realized that tourist delivery was a lucrative business. People wanted to see what they heard about the park from Albert Bierstadt’s paintings, William Henry Jackson’s photographs, and John Wesley Powell’s writings. Their tales of the park were unbelievable, and a questioning population wanted to see them with their own eyes. Students found sources (Museum of the Yellowstone, n.d.) to examine the route of the Union Pacific Railroad. The railroad map showed how guests could enter the park. Which parts of the park were easily accessible once the tourists arrived, and which parts were still difficult to access. The wonders of the park had to be witnessed to be believed.

To learn about history students needed to look at another question that involved historical study. Students asked the question about Yellowstone National Park: Where could you stay in 1904? Students found the newly constructed Old Faithful Inn welcomed visitors that year after a fire burned the former lodge. “D2.His.1.6-8. Analyze connections among events and developments in broader historical contexts” (NCSS, 2013). Travelers had different standards for accommodations at that time, but the tourist industry provided lodging and food for travelers interested in visiting a national park. While the structure still stands, guest amenities have changed across time. Students looked at resources such as the Library of Congress (n.d.), National Registry of Historic Places Inventory (Harrison, 1985), and Historic Hotels of America (2024) to find out about their topic. At the time walking along the catwalk on top of the lodge would have provided a stunning view of the surroundings for guests. Students examined compared lodging to what they expected when they traveled. Students reflected a variety of ways to travel from camping to resort experiences just as travelers in the past traveled in a variety of styles. Students considered continuity and change as they studied early tourism.

Adam moved the students’ attention to another of the properties in the National Park System – Glacier National Park. Students continued to examine the idea of the discipline of economics to investigate the question: How do you see the park? Once tourists came to Glacier National Park, they needed transportation within the park to experience the scenery. “D2.Eco.1.6-8. Explain how economic decisions affect the well-being of individuals, businesses, and society” (NCSS, 2013). Visitors needed a car with a powerful engine that could navigate mountain roads to help them see the park. They needed a knowledgeable guide to help them understand what they were seeing and to point out details that they might miss. Students used sources such as a website for the Red Bus Tour (Xanterra, 2024). Historical tourism started with the open top Red Car which allowed passengers to view the mountains but had a canvas top that could roll down in case of bad weather. The Red Car also had multiple doors and multiple seats with a capacity of ten that allowed for a reasonable price point for a semi-private guide/driver. The Red Car picked guests up at their hotel and helped historical tourists see the park with an enlightened and entertaining driver.

Another location helped students to learn about the origins of Grand Tetons National Park. The students asked: How do you start a park? Using the discipline of civics students learned about the role the Rockefeller family played in the establishment of Grand Teton National Park. “D2.Civ.13.6-8. Analyze the purposes, implementation, and consequences of public policies in multiple settings” (NCSS, 2013). John D. Rockefeller saw the land that would become the Grand Tetons National Park and was immediately captivated by it. He brought his family to the region to hike and camp with leaders in the conservation movement. John D. Rockefeller quietly purchased as much land as was needed for the nucleus of the park without anyone knowing who was acquiring the mountain and valley tracts (Lednicer, 2017). The neighbors wondered who was purchasing the land and why, but he was able to give the park to the United States Department of the Interior. Then it took an act of congress to officially make the land a park. Congress funded the development of the park through the regular appropriations of the administration within the Department of the Interior budget.

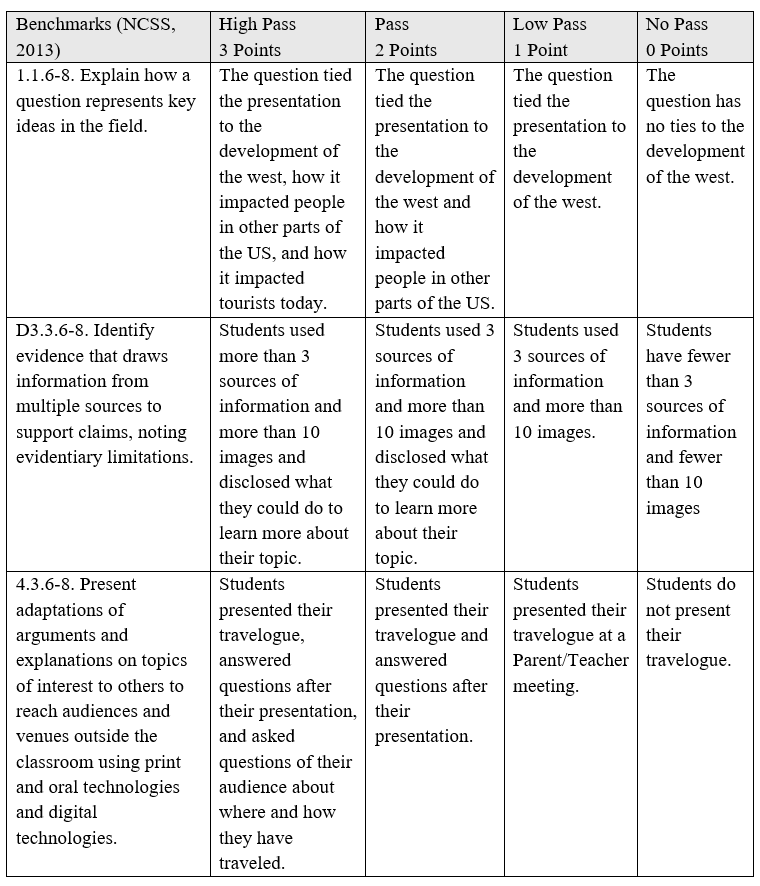

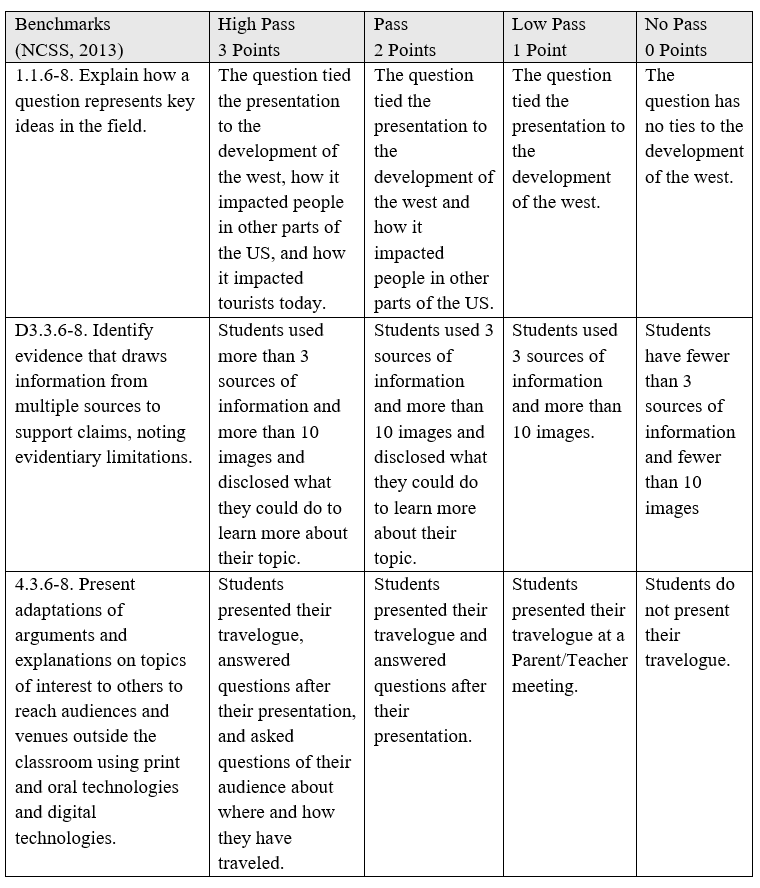

Adam brought large numbers of photographs back from the trip, and he posted the photos in groups by topic for their class in SharePoint. Students accessed the slides to create a PowerPoint presentation in a travelogue format to answer the question that they researched. Students presented their travelogues during a country market format for a parent/teacher meeting. The teacher assessed the students with the following rubrics. Adam required students to have content from one or more cells in Table 1.

Table 1: Discipline Content

In their travelogues, students raised questions about the development of the west, how it impacted people in other parts of the country and made connections to impact tourism. Students used ten or more images to illustrate their travelogue, cited three or more sources, and disclosed how they could deepen their research further in the future. Finally, as students presented their travelogues to the public, they answered questions about their project and asked their audience where and how they have traveled as a tourist.

Table 2: Project Evaluation

Conclusion and Recommendations

Secondary social studies teachers from southeast Ohio participated in an annual summer professional development program. The study's findings suggest that these opportunities positively impacted social studies education by fostering teacher growth through personal reflection and the enhancement of professional skills.

The impact of these experiences was very valuable to the participants who looked forward to engaging in professional development. The in-service depended on experts to provide content at the site of contact. The experts had extensive experience from universities and cultural institutions including government or private organizations. Teachers appreciated the in-sights provided by these people and found this an important part of the experience.

Teachers engaged with a variety of controversial issues as they visited with experts and encountered cultural locations. The controversial issues included enduring problems in democracy, the role of government in society, resource allocation questions, and environmental issues. The issues needed to be resolved by each succeeding generation as they made decisions for their generation. Teachers examined questions of aesthetics and nature as they responded to the magnificence of the land. They were bombarded by visual stimulation that they compared to the aesthetics of home. They had personal, emotional, intellectual, imaginative, and social reactions to the nature that surrounded them. The national parks helped the teachers to see the connections between cultural and environmental resources. Teachers encountered national parks as they traveled to investigate issues of land and resource management policies. They explored the relationships between the federal government and individual or the federal government and state government. Teachers expressed interest and supported the value of stewardship. They wanted the land preserved so that their students could experience the same things that inspired the teachers. They wanted the scenic and cultural wonders of America preserved for future generations and realized the controversial issues that accompanied the concept of stewardship. The social studies teachers also saw the perspective of environmental education as controversial. The ethic of conservation and a green planet flew in the face of conventional wisdom and the manufacturing-retail-disposal cycle that they encounter daily. Teaching environmental education as a part of social studies raised issues about responsible practices needed for a sustainable world.

Teachers enjoyed learning in a peer group where they investigated and explored together.

Their personal relationships with peers were both professional and personal, and they used the simile of a family to express their relation to the group. This extended kinship group shared similarities of location, profession, interests, culture, and background. These teachers also shared an Appalachian heritage that while not unique did provide both a common bond and understanding of how they lived and related to the community. They understood the context in which their students worked and how their school was situated in the community. They also compared their daily Appalachian lived experience with their professional development at the northwest continental divide. These secondary social studies teachers understood rural poverty. It cast a shadow over the life experiences, their professional environment, and the community where they taught. The professional development they encountered helped them provide insight into experiences that can inform approaches to future professional development, especially in the context of community- and place-based education.

The in-service had been successful in opening new worlds and opportunities for the teachers who participated. The results of travel experiences show that teacher travel for in-service was powerful enough to incite teachers to return to the site and to share the site with others. While not all teachers returned to visit places they encountered during in-service, those who returned to the site were accompanied by family, colleagues, or their students. Social studies in-service that was relevant to their curriculum and their professional needs attracted and sustained professional growth. The residual power of this in-service program stayed with the educators across multiple years after the initial training.