May 15, 2024

By

Kay Shurtleff

Lack of respect, high stress, long hours, low pay, high stakes tests. These are all reasons teachers give for leaving the classroom and sometimes even the profession. With so many districts operating with unfilled positions, the teacher shortage is an issue that demands attention. Rather than approaching the problem from a deficit mindset and continuing to ask questions about why teachers have left, Region 10 Education Service Center decided to take a proactive approach and find out what motivates teachers to keep doing their jobs.

It has been established that a high-caliber teacher is the best way to ensure positive student outcomes and that high teacher turnover has a negative impact on student achievement.

According to the Texas Education Agency, 11.57% of Texas teachers left the education profession following the 2021-22 academic year (Texas Education Agency). That means, however, that 88.43% of them stayed in teaching. What insights can be gained from this majority regarding what keeps them returning to school every day?

To answer this question, a mixed-methods research study was conducted. Teachers from over a hundred districts, charters, and private schools in the region were invited to participate. Presented here is an abbreviated version of the full methodology, analysis, and findings.

Review of Previous Literature

First, previous studies were reviewed to understand what researchers have learned thus far. Here, in a nutshell, is what previous research suggests are the biggest reasons teachers stay:

- A sense of purpose

- High self-efficacy

- Connection with colleagues, campus, and community

- Supportive administrators

It is, of course, more complicated than this list of four reasons. Teacher motivation is complex and does not fit neatly into categories (Chiong, Menzies, & Parameshwaran, 2017). Further, other reasons surfaced less frequently in the literature, some of which are likely related to the four reasons listed above. In keeping with the purpose of this article, salient points from previous research are summarized below.

Sense of Purpose

The single biggest reason found in prior studies for teachers’ staying in the profession was that they were able to see and believe in the potential outcomes of their work on the current and future lives of their students (Landrum, Guilbeau, & Garza, 2017; Webb, 2018). On an even larger scale, they were able to view their work as having a positive impact on society (Aria, Jafari, & Behifar, 2019; Aytac, 2021; Parr, et al., 2021; Whipp & Salin, 2018). Two separate studies (Chiong, et al., 2017; Voltz, et al., 2021) focused on teachers who had taught 10 years or longer and found that they were able to focus on their sense of purpose regardless of the external factors impacting their jobs or their campuses. In short, these teachers were able to remember their “why” throughout the day-to-day highs and lows of their jobs.

Self-Efficacy

A second characteristic of persevering teachers was that they had confidence in their ability to teach and believed they were intellectually equipped to handle the challenge (Aria, et al., 2019; Aytac, 2021; Chiong, et al., 2017; Ismail & Miller, 2020; Landrum, et al., 2017; Parr, et al., 2021; Whipp & Salin, 2018). This trait, often called self-efficacy or teacher efficacy, was seen in the literature almost as often as a sense of purpose and has been studied for decades (see Henson, Kogan, & Vacha-Haase, 2001). One study (Voltz, et al., 2021) linked teacher self-efficacy with a high-quality teacher preparation program. Interestingly, one other study (Parr, et al., 2021) found that teachers who reported having negative experiences with school when they were children were motivated by those experiences to stay in the teaching profession longer themselves! Teachers in this study seemed motivated by the idea of ensuring their students did not have the experiences they had themselves as children.

Connection with Colleagues, Campus, and Community

Just like students, teachers felt a need to belong on a campus (Aria, et al., 2019; Sudibjo & Suwarli, 2020). This sense of connection as a motivating factor was found in both rural (Whaland, 2020; Zost, 2019) and urban settings (Rinehart, 2021). Teachers who felt supported by their coworkers were more likely to stay in their jobs and, in some cases, also more likely to believe that others had respect for the teaching profession (Whipp & Salin, 2018).

Supportive Administrators

After a sense of purpose, self-efficacy, and a connection to others, teachers identified support from their campus administrators as a reason they continued teaching (Aria, et al., 2019; Lowery, 2021; Rinehart, 2021; Viano, et al., 2021; Whaland, 2020). It should be noted that three of the studies (Lowery, 2021; Rhinehart, 2021; Whaland, 2020) were recent unpublished doctoral dissertations that may signal forthcoming research in this area. Regardless, teachers expressed that when administrators respected and listened to them, they were happier in their jobs and more likely to stay. Also interesting was one small study of math teachers (Webb, 2018) which found no relationship between administrative support and teacher longevity. Teachers in that study identified their desire to help students as the main reason they stayed, regardless of their administrators or supervisors.

The four motivators for teachers to remain in their roles, as previously mentioned, are likely interconnected. Additional factors identified in the literature may relate indirectly to these motivators. For example, teachers in one study (Whipp & Salin, 2018) talked about autonomy as a reason to stay in their jobs. Autonomy may be related to strong administrative support coupled with teacher self-efficacy. Another study (Viano, et al., 2021) found school safety, student discipline, small class sizes, and access to high-quality professional learning all correlated with teacher longevity. We can speculate that those conditions were brought about by a supportive administration.

In a study that looked specifically at low-performing schools (Viano, et al., 2021), teachers stated conditions that did not influence their reasons to stay in their jobs. Among those were the school’s previous achievement data and student demographics. This is not surprising, given that teachers’ primary reason for staying was their own sense of altruism.

The Research Study

While the handful of studies that were found on why teachers keep going was a helpful beginning, it was decided to further understand what keeps teachers coming back. To that end, an exploratory sequential mixed methods research study was conducted.

Methodology

Based upon previous research, Region 10 developed its own survey which asked teachers about their motivations for staying in the classroom. The survey was administered to a test group of 30 individuals prior to general administration so that it could be validated. Following that process, it was administered to a much larger pool of teachers. After initial data collection and analysis, focus group questions were developed based upon findings from the survey. Survey participants were invited to provide their email addresses if they were interested in participating in a focus group for the purpose of delving further into their survey responses. Ten focus groups were assembled from those volunteers and focus group discussions were held over Zoom. Focus group participants were given the option to use pseudonyms if they did not wish to use their real names.

Participants

Valid survey responses were received from nearly 700 Pre-K - 12 teachers in Region 10 classrooms. Study participants included teachers from all grade levels, content areas, and experience levels, and represented participation from public, private, and charter schools. Of the 676 survey respondents, 57 (8%) were first-year teachers, and 33 (5%) had taught 30 years or longer. The average years of experience was 12.9 years. More than half (64%) earned their teaching credentials through a traditional college or university pathway, and 36% obtained alternative certification. A little more than half (55%) were PK-5 teachers, and 45% were secondary teachers. Data was not collected on the ethnicity of teachers, the size or socioeconomic status of their districts, or the subject taught. While this might be seen as a limitation of the study, refraining from collecting that data was a choice to to reassure participants that their answers were anonymous.

Findings

Because the chief purpose of this article is to engender discussion of practical solutions to the well-documented problem of teacher retention, minimal statistical analysis is shown here. A complete analysis was conducted and is available by contacting the author. What follows here is a summary of our results after analysis, synthesis, and integration of quantitative and qualitative data. The findings of this research are intended to help districts better understand the types of working environments that contribute to attracting and retaining great teachers.

It must be clearly stated that teachers in the current study strongly expressed frustration about pay and benefits, perceived lack of respect from society, and feeling overworked. Our aim is not to paint an idealized picture that long-term teachers are content with those aspects of their jobs. However, our data suggested four big factors influencing teachers who stayed in the classroom:

- Sense of Purpose in Their Work

- Joy of Working with Kids

- Connections to their Colleagues and Community

- Professional Growth and Self-Efficacy

Sense of Purpose

The single most important reason teachers gave for continuing to teach was that they believed their work made a positive difference to their communities and to society, as well as to their own students. We asked survey participants to indicate how much they agreed with the statement, I believe my job is important. Fully 98.2% of teachers (n = 663) said that they agreed or strongly agreed with that statement. Results were similar for the statement, I teach because it makes a positive contribution to society. For that question, 92.7% (n = 626) of survey respondents agreed or strongly agreed. In the words of one survey respondent,

“I teach because I love the fact that I can make a difference in a child’s life, even if it is just one child. You don’t have to necessarily understand how much you change that child’s life but just knowing I do and can, makes me continue to teach.”

The idea of purpose was further probed in the 10 focus groups. Many of them described their decision to become teachers as a calling. A high school English teacher in one of the focus groups said, “You can be a good teacher, but I always tell people there has to be a deep sense of purpose or calling. You’ve got to do it for more than just being off with your kids. You have to love working with young people first.”

Many teachers in our study were able to retain focus on their sense of purpose while at the same time acknowledging problems or drawbacks to teaching. A survey respondent put it this way:

“The job to teach is not an easy one, and it is often not valued as an important job from the outside world. I teach because I feel like I can give my students a love for learning, and a person that they know each and every day cares about them, regardless of what happened the day before. I think students deserve that person every day. My students make me happy and remind me every day that they deserve my best. I didn't initially choose the path of education, but I am very happy….”

From another survey participant came these words:

“I teach because it is my passion and what I love. I went into teaching knowing that the pay would not be adequate for the amount of work, pressure, and importance of the job, but I care about the wellbeing of society, so I do it.”

Subsumed within the theme of sense of purpose was teachers’ belief in their own ability to teach effectively, or self-efficacy. One survey respondent wrote,

“I choose to stay in education because I feel it is my calling. Education needs great teachers. Great teachers become great with experience. Too many teachers are leaving after 3-5 years. I choose to stay because I feel that my experience and talents are needed more than ever. I'm at my prime and can provide an exceptional education to my students because of what I've learned over the years. We would want a well-experienced doctor taking care of our case, and the same applies to a student's education. We need our best and most experienced taking care of our ‘cases.’”

In focus groups, teachers reported asking students for feedback, discussing problems of practice with their peers, and observing student behaviors as ways they gauge their effectiveness.

Joy of Working with Kids

Closely related to the idea of purpose, the joy of working with kids surfaced as a major reason for teacher longevity. In the survey, teachers were asked to indicate how much they agreed with the statement The relationships I build with my students make me want to continue teaching. Less than 2% of respondents disagreed with that statement. One survey respondent wrote,

“My most important goal in teaching is to connect to students and build positive relationships with them. Obviously, I would love for them to embrace the content more but at the end of the day if they are better human beings and can be more of a positive contribution to society by the time they leave high school then I will feel like I've done a good job.”

Teachers also talked about classroom “aha moments” and about being able to instill an excitement in their students about the subjects they teach. They described building a supportive classroom culture, sharing inside jokes with their classes, the ways students make them laugh, and the gratification that comes when students grasp a difficult concept. Even beyond that, they talked about the potential they see in their students and how much they value each of them as people. A high school teacher in one of our focus groups dismissed the idea that kids are not interested in learning. She stated that although they might act like they want to be “phone heads,” they are actually “smart and bright and able to think through problems.” In each focus group teachers spoke with optimism about the future that the students currently in their classes will build. One middle school teacher enthusiastically cautioned, “Don’t sell kids short!”

Additionally, teachers expressed great fulfillment in reconnecting with former students, appreciating those who reach out years later or who maintain ongoing communication. Several teachers talked about specific students who had returned and shared the comments and feedback those former students had given them. An elementary school teacher in one of our focus groups said it like this:

“I get to see their pre-adult life. Former students still contact me and want advice. Some of them consider me as their teacher mom, want career advice or to talk about their courses. Those connections you can’t get anywhere else, and it shows that you’re there for a reason.”

Connections to Colleagues and Community

Just as it did in previous studies, collegial relationships proved to be important to teachers in this study. The survey asked how important colleagues and teammates were to teachers' decisions to stay in teaching. Most survey respondents (87%) indicated their coworkers were important, and survey comments reflected those sentiments as well. For example, one teacher said, “I teach because I can be part of a team of educators, working toward an honorable goal. I teach to make a difference in a child’s life.” Likewise, in focus groups, they said things, such as, “Good colleagues are everything. I’d rather have good colleagues than a good administration. If you don’t have someone to go through this with, it’s an island, and an island is very lonely.” Some of them mentioned both the formal and informal mentors they had as early career teachers and the importance of mentoring current early career teachers to build capacity within their schools and the profession.

Professional Growth

For the present study, we define professional growth as the desire for opportunities to learn and grow professionally in both content knowledge and pedagogy. Questions around professional growth were not included in specific survey questions, but the topic did surface in the open-response comments on the survey so often that we asked about it in our focus groups. For some participants in our study, professional growth stemmed from a love of their subject as a student themselves and grew into the desire to share their own knowledge and enthusiasm for that subject. One participant stated, “I had an average experience in high school with the subject that I teach, but I had an amazing experience in college with the same subject. I want to provide an amazing experience to students when they are in my classroom, including what I teach, how I teach it, and relationships I build with my students.”

For others, such as an elementary teacher who recently changed the subject she teaches because of a shortage of teachers in her district, that meant simply enjoying the challenge of taking on something new which teaching affords. In a focus group, a high school teacher recounted some advice she had given to an unofficial mentee on her campus: “Teachers have to have a growth mindset and look for ways to learn and keep up with research. There has to be a willingness to change and a commitment to your own professionalism.”

Put another way by another participant, “I joined the profession because it was something I felt I was born to do. A ‘calling,’ I would say. I have stayed because I've had the opportunity to continue my education and teach several different grades and subjects.”

The Role of Administrators

Noticeably absent from the reasons teachers gave for continuing to teach was the teachers’ campus administrators. In our sample, 33% of teachers said they would consider following their administrator to a different campus, and 72% said they felt supported by their administrators. When we probed further during focus group discussions, teachers explained that while they appreciated supportive administrators, most teachers did not base their job decisions on the campus administrator. Three underlying reasons formed their opinions: teachers’ perception that the administrator’s tenure on the campus would be short; teachers’ perception that their administrators did not have enough classroom experience to understand their jobs; and teachers’ reliance on their teams and colleagues as a source of support. Most teachers agreed that a strong campus administrator had the potential to keep teachers in the classroom, but few stated that they had experienced that working environment. One focus group junior high teacher stated, “When a principal actually makes you feel like you matter in a building, you’re going to do a lot for them.”

Reasons for Leaving a Campus or District

We also asked teachers whether the five factors found in previous research might contribute to their decisions to either stay or leave a campus or district. Listed in their order of importance, those factors appear below. Percentages represent the number of survey participants who stated that the factor listed was extremely important or somewhat important.

- Campus or District Discipline Procedures (98%)

- Pay & Benefits (97%)

- Class Size (97%)

- School Safety (95%)

- Access to High Quality Professional Learning (80%)

None of the factors were shown to be unimportant; however, there is a marked difference between access to formal professional learning and the other four.

How Can We Keep Teachers?

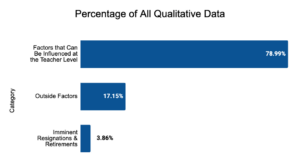

The data revealed other insights about long-term teachers, but none appeared to be as meaningful as those described above. When synthesized, all the discreet ideas from qualitative data from both the survey and the focus groups, it was found that 79% of all the ideas expressed were related to conditions that can be cultivated without policy or staff changes. To be clear, teachers did absolutely express a desire for better pay and benefits, more respect, and better work/life balance. But the data showed that there are other drivers at work that districts may be able to address quickly.

While all educators would welcome an increase in pay and benefits for teachers, that solution would require major budget and policy changes. There are other changes that districts might implement in the short term. The collected data can be summarized into three overarching categories, each with its corresponding themes and codes derived from the integration of both quantitative and qualitative findings. Note that percentages refer to the percentage of total discreet ideas from qualitative data that pertain to each theme. They are shown to gain a sense of how weighty each theme was on the minds of participants in the study and are not an attempt to quantify qualitative data.

CATEGORY I - Factors that Can Be Influenced at the Teacher Level (78.99%)

Theme 1 - Connection with a Sense of Purpose (32.49%)

- Importance of the Profession

- Teacher’s Self-Efficacy

- Sense of Joy from Teaching

- Past Experiences with their Own Teachers (both positive and negative)

- Career Change to Teaching as a More Satisfying Career

Theme 2 - Opportunity to Work with Kids (25.85%)

- Building Relationships with Kids that Helped them Learn and Grow

- Appreciation for their Students’ Innate Value and Abilities

- Reconnecting with Former Students who Returned

Theme 3 - Connection with Colleagues (13.53%)

- Connection to Community

- Connection to Coworkers

- Influence of Parent or Teacher

Theme 4 - Personal Growth (7.13%)

- Love of the Subject They Teach

- Continuous Learning

- Teacher Leader Opportunities

- Opportunities for Promotion to Administration

CATEGORY II - Outside Factors (17.15%)

Theme 5 - Convenient Career Choice for Family (13.65%)

- Work Location and Schedule

- Ability to Teach at their Children’s School

Theme 6 - Autonomy & Trust (3.50%)

- Trusted & Supported by Administrator

- Autonomy in Classroom

CATEGORY III - Imminent Resignation or Retirement (3.86%)

Theme 7 - Leaving or Retiring (3.26%)

Theme 8 - Belief that Teaching Was their Only Employment Option (.61%)

As shown in the graph below, most of the reasons teachers gave for staying in the classroom were related to elements of their jobs that can be cultivated or changed on individual campuses without scheduling or budgetary changes.

Concrete Action Steps

Given the findings of the current study, as well as previous studies, seven high leverage practices that districts might adopt to improve teacher retention in their districts are recognized. Through the Empowering New Teachers Mentor and Induction Program and the Supervision and Leadership Development team, Region 10 ESC is in the process of working with districts to implement these practices.

Practice 1: Help teachers reconnect with their sense of purpose. Based on the current study and previous literature review, this is the single most effective way to increase teacher retention. It is, however, also the most difficult to define and quantify. In this study, 98.2% (n=663) of survey respondents said that they believed their jobs were important. Over and over, the participants in this study stated that they loved working with kids, they saw great potential in their students, and they believed that teaching was the most important thing they could do. They also stated that while they firmly believed their jobs were critical, they rarely or never heard their leadership talk about the critical role of teachers. One simple step campus and district leaders can take is to explicitly talk about the importance of teachers to the teachers themselves.

Teachers in the study repeatedly discussed the joy that came from hearing from former students and identified those interactions as affirmations that their work was valuable. Campuses and districts might consider proactively contacting former students and inviting them back to visit their former teachers.

Practice 2: Increase pay and benefits for teachers. In the words of one of the teachers in this study, “I have to work two jobs to support my life with little ability to save or purchase large-scale items. I can't support buying a house to build my wealth. This is an issue that plagues a lot of teachers, which makes the profession unrealistic to grow and thrive.” Educators, legislators, and other stakeholders across the country frequently discuss and debate this topic. Many of the potential solutions for increasing base pay are beyond the scope of this article. However, districts can take other steps to increase fringe benefits. For example, Region 10 Education Service Center currently provides mental health and telehealth benefits to employees, as well as a matching contribution program for a retirement fund. Some districts are offering similar benefits. During the last two years, it has become more common for districts to offer a signing bonus for early career teachers. Caution should be taken by those districts to ensure that mid and late career teachers receive commensurate compensation.

Practice 3: Implement an effective program to manage student behavior. When asked the extent to which the campus discipline protocol affected their decisions to remain at their campuses, 82% (n=526) of teachers who responded to the survey stated it was extremely important, and 16% (n=101) stated that it was somewhat important. Districts and campuses should make a concerted effort to develop a discipline plan, communicate it to all stakeholders, and consistently and transparently implement it. ESAs can support this effort by educating districts about the importance of this issue and about best practices regarding student behavior.

Both teacher pay and student discipline are complex issues that require long-term solutions that lie beyond the scope of this article.

Practice 4: Celebrate teachers. Study participants talked about how discouraging it was to hear politicians, parents, and the public in general disparage their profession. Districts can start to combat the problem by publicly defending their teachers against critics. They might also be intentional about the way they communicate to teachers the value they place on them. For example, campuses sometimes create initiatives to make their students feel valued by referring to them as scholars instead of students, yet similar efforts to distinguish teachers as a group of valued individuals are far less common. Teachers talked about the difference it made when they believed their administrators saw them as professionals. “I spend a lot of time feeling like I’m not doing a good job,” stated one junior high teacher. She continued by explaining that although her recent observation and evaluative feedback was positive, she rarely received feedback from campus leadership at any other time. Multiple teachers expressed similar feelings about being unseen or inadequate.

The following statement was made by a survey participant: “More money would be nice, but more respect, support, and freedom in our classroom would add up to more than a barely higher salary.” Campus and district leadership can immediately address concerns by following this advice.

Practice 5: Celebrate kids apart from their academic or athletic achievements. Career teachers talked about how often they thought about their students when they were not in the classroom and how rewarding their relationships with their students were. Of the survey participants, 94.8% (n=640) said that building relationships with students caused them to continue to teach. A teacher in her 26th year stated, “I have had eight principals--some good and some not so good. The kids are what keeps me coming back. They are the fun part.” Another veteran teacher of advanced math classes stated that his main job was “to help the kids learn about themselves.” He continued, “The relationship is more important than the 2nd derivative of a cosine curve.”

Although good teachers naturally build relationships with their students during the class period, campuses and districts could build occasional periods of time into the school schedule for teachers and students to simply build trust, play games, and get to know each other.

Practice 6: Find ways to increase teacher self-efficacy. Professional learning opportunities for teachers exist almost everywhere: individual districts, education service agencies, state education agencies, private vendors, free and fee-based online courses, instructional materials publishers, museums, art galleries, and technology companies. Rarely, though, do those entities offer professional learning in self-efficacy. A body of research (see Bandura and others) supports the value of teacher self-efficacy, yet it is rarely addressed in a systematic way. In this area, ESAs can take the lead in offering professional learning to teachers, as well as supporting districts in building their own capacity to strengthen their teachers in this area.

Practice 7: Provide unstructured time for teachers to be with their colleagues, to observe and learn with and from each other, and to learn at conferences and other professional learning events. The quantitative as well as qualitative data in this study overwhelmingly suggests that the support and camaraderie teachers get from their peers is key to their job satisfaction and longevity. One teacher, a 27-year veteran, summed up the sentiments of most study participants when he said teachers would greatly benefit “if leadership could find a way to create opportunities for colleagues to be together to commiserate and support.” Of survey participants, 87.5% (n=573) stated that their colleagues were important to their perception of their jobs. In contrast, 36% (n=136) stated that they would follow their administrators to another campus.

District leadership and ESAs can provide time beyond data meetings and professional learning communities (PLCs) for teachers to collaborate authentically and organically. Rather than giving them tasks to do, districts and ESAs might consider facilitating discussions among teachers to help them work together to solve problems of practice. Before that can happen, time should be allotted for teachers to get to know each other.

As is true of all research projects, new research questions have sprouted from this study. Investigation of the differences in attitudes and needs of early career teachers is needed. Additionally, considering the findings in the current study, various mentor programs should be studied to determine whether they impact new teacher in the areas investigated here.

Every day, teachers defy the odds by motivating and inspiring themselves, each other, and their students. Solving the teacher shortage has no immediate solution. Within immediate grasp, however, are solutions that ESAs and districts might immediately address.

References

Aria, A., Jafari, P., & Behifar, M. (2019). Authentic leadership and teachers’ intention to stay: The mediating role of perceived organizational support and psychological capital. World Journal of Education, 9(3), 67-81.

Bandura A. (1997). Self-efficacy: the exercise of control. W.H. Freeman and Company.

Bland, J. A., Wojcikiewicz, S. K., Darling-Hammond, L., & Wei, W. (2023). Strengthening pathways into the teaching profession in Texas: Challenges and opportunities. Learning Policy Institute. https://doi.org/10.54300/957.902

Aytac, A. (2021). A study of teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs, motivation to teach, and curriculum fidelity: A path analysis model. International Journal of Contemporary Educational research, 8(4), 130-143.

Chiong, C., Menzies, L., & Parameshwaran, M. (2017). Why do long-serving teachers stay in the teaching profession? Analysing the motivations of teachers with 10 or more years’ experience in England. British Educational Research Journal, 43(6), 1083-1110.

Doan, S., Steiner, E. D., and Woo, A. (2023). State of the American Teacher Survey: 2023 Technical Documentation and Survey Results. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2023. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA1108-7.html.

Henson, R., Kogan, L., & Vacha-Haase, T. (2001). A reliability generalization study of the Teacher Efficacy Scale and related instruments. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 61(3), 404-420.

Ismail, N. & Miller, G. (2020). High school agriculture teachers' career satisfaction and reasons they stay in the teaching profession. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 8(1A), 95-103.

Landa, J. (2022, August). Employed teacher attrition and new hires 2007-08 through 2021-22. Texas Education Agency. Retrieved at https://tea.texas.gov/sites/default/files/employed-teacher-attrition-and-new-hires-jbl220825.pdf

Landrum, B., Guilbeau, C., & Garza, G. (2017). Why teach? A project-ive life-world approach to understanding what teaching means for teachers. Qualitative Research in Education, 6(3), 327-351.

Leech, N., Haug, C., Rodriguez, E., and Gold, M. (2022). Why teachers remain teaching in rural districts: Listening to the voices from the field. The Rural Educator, 43(3), 1-9.

Lowery, C. A. (2021)., Currently employed teachers' perceptions of the reasons teachers leave the profession or stay: A Q methodology study Electronic Theses & Dissertations. 549.

https://digitalcommons.tamuc.edu/etd/549

Parr, A., Gladstone, J., Rosenzweig, E., & Wang, M. T. (2021). Why do I teach? A mixed-methods study of in-service teachers’ motivations, autonomy-supportive instruction, and emotions. Teaching and Teacher Education, 98, 103228. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0742051X20314190

Rinehart, L. E. (2021). Urban teacher job retention: What makes them stay? (Doctoral dissertation, Purdue University Graduate School).

Sudibjo, N., & Suwarli, M. B. N. (2020). Job embeddedness and job satisfaction as a mediator between work-life balance and intention to stay. International Journal of Innovation, Creativity and Change, 11(8), 311-331.

Texas Education Agency. (n.d.). Employed teacher attrition and new hires TGS210519 - Texas Education AgencyTex. Texas Education Agency. Retrieved April 24, 2023, from https://tea.texas.gov/sites/default/files/employed-teacher-attrition-and-new-hires-tgs210519.pdf

Viano, S., Pham, L., Henry, G., Kho, A., & Zimmer, R. (2021). What teachers want: School factors predicting teachers’ decisions to work in low-performing schools. American Educational Research Journal, 58(1), 201-233.

Voltz, D., Loder-Jackson, T., Sims, M., & Simmons, E. (2021). Where Are They Now?. Journal of Urban Learning, Teaching, and Research,16(1), 89-117.

Webb, A., & , (2018). A Case Study of Relationships, Resilience, and Retention in Secondary Mathematics and Science Teachers. Journal of Educational Research and Practice, 8(1), 1-18.

Whaland, M. E. (2020). Why rural teachers stay: Examining teacher retention and attrition in New Hampshire’s rural schools. (Doctoral dissertation, Plymouth State University.)

Whipp, P., & Salin, K. (2018). Physical education teachers in Australia: Why do they stay?. Social Psychology of Education, 21(4), 897-914.

Zost, G. (2019). An examination of resiliency in rural special education. The Rural Educator, 31(2), 10-14).

Dr. Kay Shurtleff, Research & Evaluation Analyst, Region 10 Education Service Center

She can be reached by phone at 972-348-1010 or by email at kay.shurtleff@region10.org.